The way that nature is defined is the negative space around which a culture forms itself

Elvia Wilk

*

The way that nature is defined is the negative space around which a culture forms itself.

Today we continually try to erode the conceptual division between nature and culture. We realize that continuing to consider ourselves separate from the environment has made us feel we have the right to disregard it. Our fates are intertwined, and we can have no illusions about our impact.

At the same time, we know that the only way to preserve nature is to define it as such. We have to cordon it off from our influence if we are to stall human impact on it – on that which we assume would have existed without us. Paradoxically, reinforcing the theoretical interdependency of nature and culture demands reinforcement of their physical separation.

In 2008 the residents of the Alaskan island of Kivalina sued Exxon Mobile, eight other oil companies, 14 power companies, and one coal company for their roles in causing water pollution and rising sea levels – the effects of which will likely drive out the already marginalized native community on Kivalina from their homes in the next decade. This was the first environmental lawsuit ever filed by a “discreetly identifiable victim.” It’s only possible to pursue litigation on behalf of the environment if there exist a human plaintiff and defendant.

To care about humanity now necessarily includes caring about the environment. Humanitarianism implies environmentalism, and vice versa.

The governing body of the shrinking islands of the Maldives prefers to ask nicely rather than antagonize. The former president of the 28 islands in the Indian Ocean, which are similarly threatened by rising water levels, has made emotional appeals on American television shows, imploring the international community (especially those in rich western countries) to lower carbon emissions on behalf of the Maldives’ population before their homes submerge.

Efforts to preserve nature on behalf of people rely on determination of guilt: either litigious or emotional or both. (When is law ever unemotional?)

Some climate scientists have suggested that the Maldives’ situation may not be as dire as it’s been made to sound. But alarmism about rising sea levels has also had the positive economic effect of attracting foreign investment and development aid into the country. A booming tourism industry thrives in the meantime. This economic stimulus indirectly supports a repressive governmental regime. Human rights abuses crop up in the news alongside climate change reports.

Environmental alarmism, no matter how warranted, prompt us to consider the agendas on all sides, and to examine our priorities regarding human well-being in the short and long term.

*

The way that nature is defined is the negative space around which a culture forms itself.

Like so many brands of lifestyle politics, the rhetoric of environmentalism often appeals to the emotions of fear and guilt. Nature is framed as a powerful force beyond human comprehension that we must respect lest it destroy us. The gist of this story is “don’t treat nature badly or ‘she’ will have her revenge.” The aim is to reinforce the emotional sense that nature is more powerful than humans are, and that the proper response to natural forces (whatever they are) is respect, reverence, and ultimately fear. Determination of guilt naturally follows.

The Western obsession with the twin stories of paradise and disaster, the Eden and the Flood, romanticizes nature’s power and therefore emphasizes our insignificance in the face of it. But at this point we are no longer insignificant. We have altered it beyond comprehension. In the Anthropocene, are the emotions of guilt and fear still appropriate or effective reactions at all?

There are several obvious reasons to rely on those emotional provocations. We might assume that it’s because the only way to get people to “wake up” and stop driving their cars, subdividing land, flocking to cities, littering, etc. is to scare them into what will happen if they don’t. The rising tides will envelop us all! If we aren’t attuned to the possibilities in advance by confronting the wilderness and understanding its power, we won’t be scared enough of the consequences to change our behavior.

This is in accordance with the theory that “awareness raising” is the first step to battling the primary threats to humanity: natural forces, physical health (body is another aspect of nature), armed conflict. Raising awareness usually includes raising money too. Change pours into little plexiglass containers at café counters and gets sent to the Maldives. Or somewhere.

Yet if nature is to be feared, it is also to be dominated. Provoking fear of the power of nature is precisely what gives credence to the ideology of its domination. If something is scary, what is the more human response: calm conversation or violent confrontation?

There may be a common denominator between the rhetoric of conservationists and those who exploit the environment for profit. Both instrumentalize the meaning of nature for their own ideological goals. Preservation and domination rely on the same myths of wilderness and fear that slot into and strengthen each other. This is mutually reinforcing, setting up a deadlocked dichotomy. Ideology produces counter-ideology. Defining nature is a de-facto ideological decision. And facts are distorted on all sides.

*

The way that nature is defined is the negative space around which a culture forms itself.

Like the water surrounding an island.

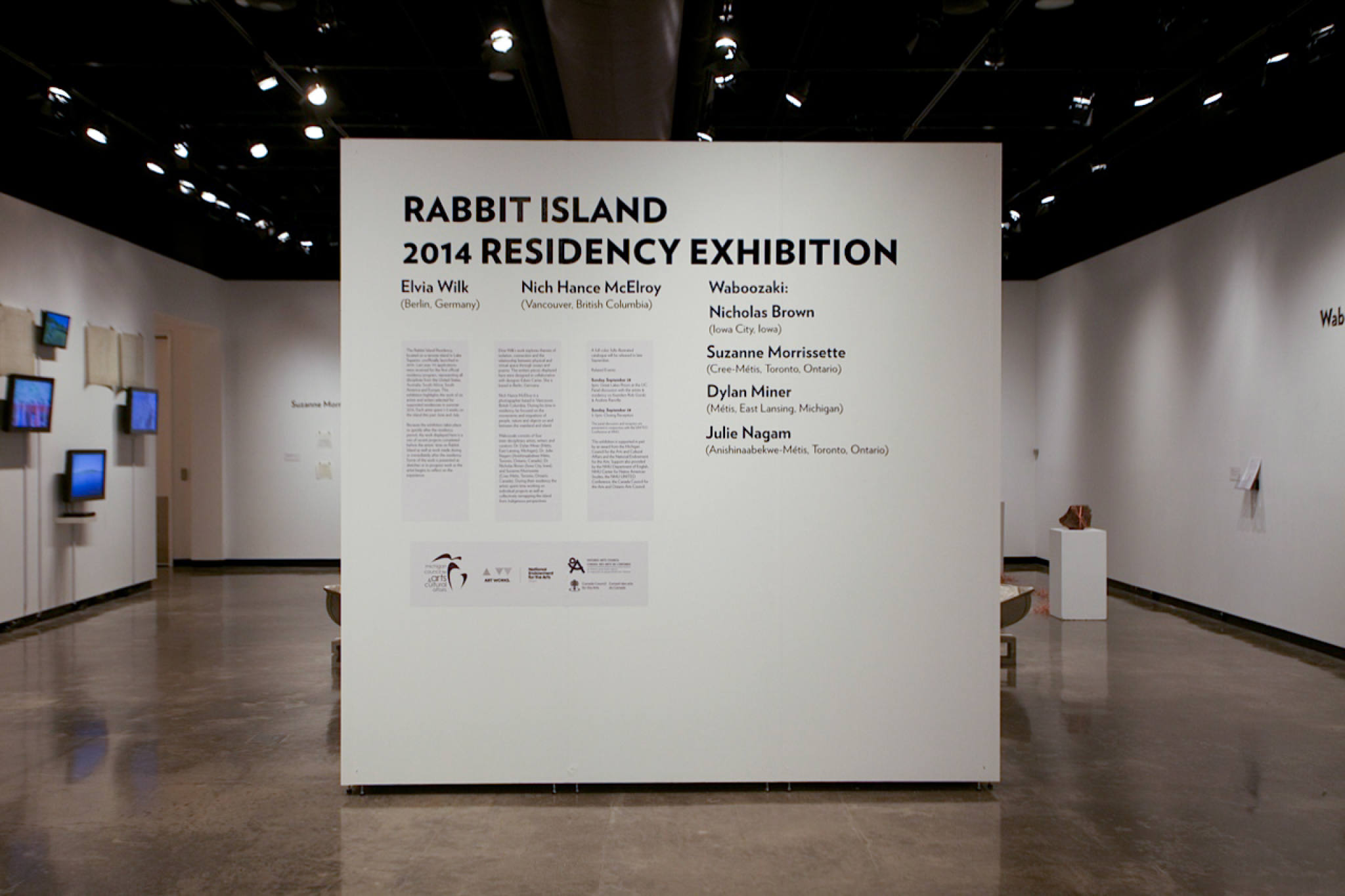

I spent eleven days on Rabbit Island in June 2014. Eventually nature expelled me: after six days of below-freezing temperatures and storms I decided I’d had enough. Instead of remaining on the island I boated back to the mainland and spent two weeks in the Copper Country on the Keweenaw Peninsula.

In this area, the former copper mining industry remains a central mark of cultural identity and heritage. The mines initially brought masses of European immigrants to that area in the second half of the nineteenth century, and despite the fact that the mining companies pulled out nearly fifty years ago, the history and mythology of the mines pervade.

Mining is one of the clearest examples of what it means to tear into nature and get what you need from it for economic gain. Alongside exploitation of the land, the mining industry in the Copper Country also exploited the people it employed, as evidenced by the long and contentious (violent) history of unionization efforts in the area. Again, when exploitation of nature and exploitation of people coincide, environmentalism and humanitarianism have similar goals.

Yet the copper industry is remembered primarily and accurately as a positive economic force. The influential Calumet and Hecla Mining Company was a particularly prosperous one, and when it pulled out in the late 60s, after 30 odd years of dilly-dallying and struggling with the unions, the area slid into a steep economic decline. This contrast sets up a powerful opposition between past and present: boom and bust.

Today, a nascent tourism industry on the Keweenaw dependent upon both nature and cultural heritage represents a potential new, long-term, sustainable economy. This would be an economy dependent on preservation, both of nature and culture.

Yet in the short term, neither a local museum or a national park has the employment power of the mining industry. And in a world of diminishing resources and escalating prices, the re-opening of the mines in the next century is probably inevitable. Positive memories of the mining industry due to its association with prosperity have created a dichotomy between environmentalists – those who would reject re-opening the mines due to its deleterious environmental effects – and the working class, who want and need jobs now.

Preservationism becomes a class issue. Prioritizing it is a privilege, a tree-hugging thing.

Mining is necessarily a boom and bust situation. Resources are finite, and economies fluctuate. When it’s no longer profitable to go to the trouble to mine the metal, or when it runs out completely, another bust will follow. In turn, this reality allows those without pressing economic needs to frame the working class as short-sighted.

According to a book I read at the Calumet historical archive, most Native American populations living on the Keweenaw Peninsula before the mining industry arrived were migratory, leaving the area in the winter when it became too harsh. These cultures saw no reason to endure the brutal seasons, whereas the mining settlements relied on consistent economic productivity – and therefore perpetuated the myth of “braving” the natural surroundings to dominate nature, literally to extract quantifiable value from it. (In comparison, tourism is a sissy, seasonal industry: it depends on weather rather than overcoming it.)

I don’t say this to reinforce the classic assumption that native peoples “respect nature” as opposed to westerners who only want to exploit it. I want rather to reinforce the links between fear, domination, and industry, in order to support the hypothesis that guilt and fear are common denominators between the goals of preservation and domination.

*

The way that nature is defined is the negative space around which a culture forms itself.

My short stay on Rabbit Island was physically uncomfortable. I was extremely cold and very wet. At times I found the storms intimidating. Some noises from the forest were threatening. One bird call in particular gave me terrible dreams. These physical and psychological inconveniences did not instill in me a new reverence for nature’s raw power: they made me wonder why I had assumed that inconvenience would pave the path towards understanding. I wondered what being uncomfortable has to do with understanding nature. I wondered if I should feel afraid of something.

Am I communing with nature on a beach vacation with a shower and a bed nearby, or am I only communing when cold, wet, and alone? It is only “natural” when it is inconvenient? Who decides what is convenience and what is necessity?

The weather to some extent affects my daily life in Berlin, where I live for most of the year. Like the winters on the Keweenaw Peninsula, Berlin winters are miserably dark and icy and cold. Everyone slips on the ice and gets the flu. But in Berlin I have a heated, four-walled apartment. If the heating breaks in my building, I can go stay at my friend’s house down the street. If I run out of money to pay my heating bill, I can ask my flatmate for help or take a handout from my parents.

The difference between my time on Rabbit Island and my daily life was not the power of nature, it was lack of infrastructure. To put myself alone on an island with no infrastructure and no social network was a privileged choice; I spent many resources to get there (an airplane trip is not only expensive but abhorrent in terms of environmental impact) and to enter a situation artificially constructed to be difficult.

Varying levels of “convenience” have been employed on the island over time. Once there was a pump installed to pull drinking water from the lake. Later it was deemed unnecessary and removed. Its removal was no less artificial than its construction.

For me, lucky as I am, living for a very short time without running water or adequate protection from the elements was a human choice, informed by a cultural circumstance that suggests that discomfort is the way to a greater understanding of nature’s Power. I suspect that this belief stems from the fact that many of us feel guilty for not being afraid of nature at all.

Yet the desire to put oneself in an extreme circumstance implies the parallel desire to dominate or overcome it, perpetuating a cycle of fear, guilt, and exploitation. I was able to see myself as a part of this cycle.

Climate change is certainly making our environmental realities increasingly extreme, and we in the wealthy world can’t become strangers – via our comforts – to what serious weather conditions will mean for everyone’s existence. Awareness of what is in store is a vital step towards making changes, which will have to be drastic. But the nature of this awareness is important: awareness isn’t just a yes-or-no thing.

Confrontation with the elements raised my awareness of my own inherited cultural beliefs more than of my specific natural surroundings. The nature of my awareness arrived as I examined the peculiar and potent mixture of guilt and triumph that I was feeling, in which I recognized an awfully Anthropocentric view towards nature.

This awareness was reached when I returned to the mainland, while I was sitting in a warm bathtub in a pleasant room, watching the storm rage outside the windows.

Both my critical and creative writing practices converge at the intersection of art, architecture, and networked technology, exploring the relationships between physical and virtual space. Through critical writing about art and architecture and an expanding poetry practice, I find ways to merge subjects and bridge disciplines. I follow curiousity rather than prescribed paths of action, situating each project in specific context that suits it best – books, periodicals, websites, exhibitions, and performances. I want to merge the function and the aesthetics of language, investigating the places between linguistic logic and the creative pathways that non-logical uses of language make possible.

During a residence period on Rabbit Island I would like to pursue a two-fold project. First, I propose to write an essayistic piece about my experience living on the island, to be published in one of several periodicals with which I have regular contact and have previously contributed to. The text, approximately 5,000 words, will focus on questions I have begun investigating thus far in my work, beginning with the politics of isolation within today’s networked society. How has my relationship and understanding of nature been affected through the evolution of the technologies I use? Where is the dividing line between the “natural” environment and the created, virtual one?

In this text I will also contemplate the way time passes in my daily life on and off the computer. Time often feels like it is accelerating rapidly through a barrage of constant information online and off. What could it mean for me, personally, to slow this flood? Do I have to physically isolate myself to re-align the passage of time with my own internal bodily rhythm? I anticipate that living in close interaction with the flora and fauna of the island will shift my center of gravity, which will in turn affect the pace and tone of the writing I make.

Unlike most previous texts of mine, this article will be written in the first person, with a special focus on the aesthetics of the language -- sonic and visual -- and the way it mirrors the experience it depicts. I want to further merge my poetic practice with my critical work, creating a narrative arc through the lens of first-person voice rather than relying on logical deduction or argument.

My second project will be a small compilation of poems to be self-published in an edition in 100 after the residency period is completed. This collection of 10-15 pieces will provide an alternate way for me to process the texture and quality of my physical presence on Rabbit Island. I want to see how the ideas I process in my essay develop if I am given the time to pursue both essayistic and poetic practices at once, and vice versa. This is not a luxury I am afforded in my daily life due to the demands of constant written work that a writer is required to produce – one has to prioritize one practice over another, and define one’s work via a career path. Through networked technology, constant input must be matched by constant output.

Being at Rabbit Island would give me the opportunity to use the natural landscape – rocks, trees, herons – as a starting point for the artistic research of the writing process, rather than beginning with the internal world of my laptop screen as I do during my daily urban life. Perhaps isolation is impossible today, but how would being surrounded by water on all sides for a chunk of time alter my mentality, my constant need for back-and-forth interaction through a server? Fittingly, water serves as both content and metaphor in much of my writing. I’m interested in juxtaposing its fluidity with the dichotomous, mathematical structure of our networked existences, and the often-rigid physical architecture characteristic of urban space. Does information “flow” through these systems like water? Are concepts so liquid as they appear?

I have more than enough experience in the outdoors to handle the demands of living on Rabbit Island. From my extensive worldwide travels – including days and weeks of boats, tents, and mosquitoes – I’ve found that becoming self-reliant in a new environment is the most generative creative process there is. Furthermore, I am extremely excited about the prospect of working in conversation with the other members of the program in this context.

During the residency period I hope to explore the way my various formal approaches to language interact, fuse, or separate without a singular, pressing assignment at hand – without a function to fulfill. I would like to find my own rhythm and way to move through time, and see what kind of work emerges. And in a cyclical process, this life experiment will become the content of both projects I create.